The issue with predicting you have trauma

'Trauma focused therapists' don't talk enough about the predictive brain

Toddlers often don’t even know when they’re hurt. They have a mild tumble at the park and immediately look at their parents to figure out how to think about what just happened. If Mommy looks worried and begins rushing over to scoop up the kid, that’s a good sign to the kid that he’s on the brink of death and he begins crying. If Dad’s expression barely changes while telling the the kid ‘you’re fine,’ the kid will probably just keep on playing.

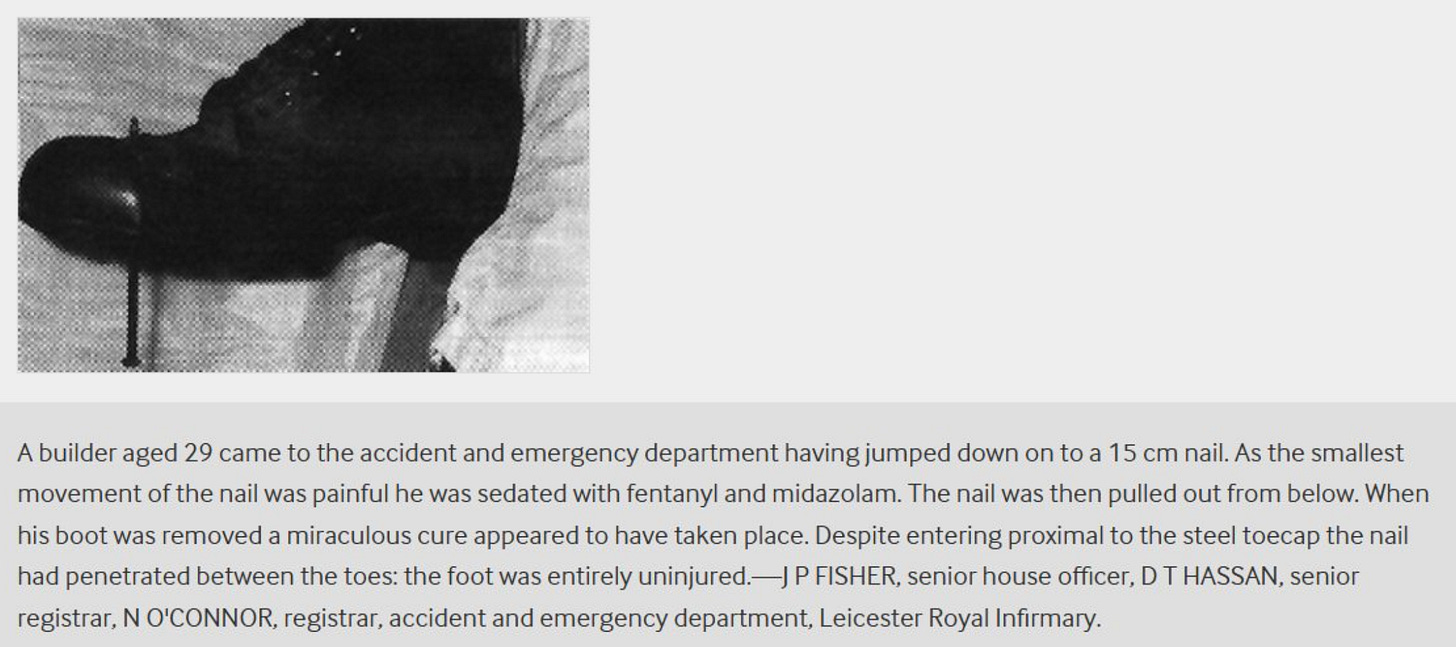

In the 1990’s, a 29 year old man wearing heavy-duty steel-toed boots was working at a construction site. The boots are designed to protect the toes from being crushed by falling wooden planks, a misplaced sledgehammer swing, or poorly maneuvered wheelbarrows. The man discovered the boots’ weak point when he jumped down from a platform directly onto a 15 cm nail. The nail easily pierced through the bottom of the shoe and through his foot. In terrible pain, the man quickly made his way to the emergency room. The smallest movement of the nail created waves of unbearable pain, so they sedated him with fentanyl and midazolam. With the man heavily sedated, the sober doctors were now free to have a yank at the nail. Surprisingly, there was no blood on the nail nor any inside his boot. On closer inspection, the doctors realized the nail penetrated straight through the boots and right between the man’s toes. His foot was completely uninjured.

The pain the man felt was real, but the injury wasn’t.

This anecdote from a 1995 paper in the British Medical Journal is often used to illustrate how weird pain is. Cognitive scientist Andy Clark used the example in his presentation about the predictive nature of the brain at The Royal Institution. What the boots illustrate is not only the predictive nature of the brain, but just how powerful it is.

You’ve probably heard of the placebo effect. It says that the mere expectation of getting better will lead to an actual improvement in one’s affliction, physical or mental.

The nocebo effect says the opposite. The expectation of a negative outcome leads to actual physical symptoms or actual mental afflictions like anxiety, stress, or depressed mood.

At some point we have to ask:

・How many people are suffering from the thought that trauma* makes them suffer?

・How often is ‘trauma focused therapy’ only working because the patient believed in the story about trauma in the first place?

That is: what if the trauma narrative is merely a nocebo and the trauma therapy is merely a placebo?

*PTSD is a real thing. There are certainly people who involuntarily suffer from horrid past experiences.

Though, what about the people who didn’t think they had trauma until they were told they did?

Gabor Mate says “Trauma is underneath all human dysfunction,” which includes everything from ADHD and addiction to more vague things like “confusion” and “separation from the self.”

If that’s correct, then the logical conclusion is to start searching for your own hidden trauma so you can heal it, right?

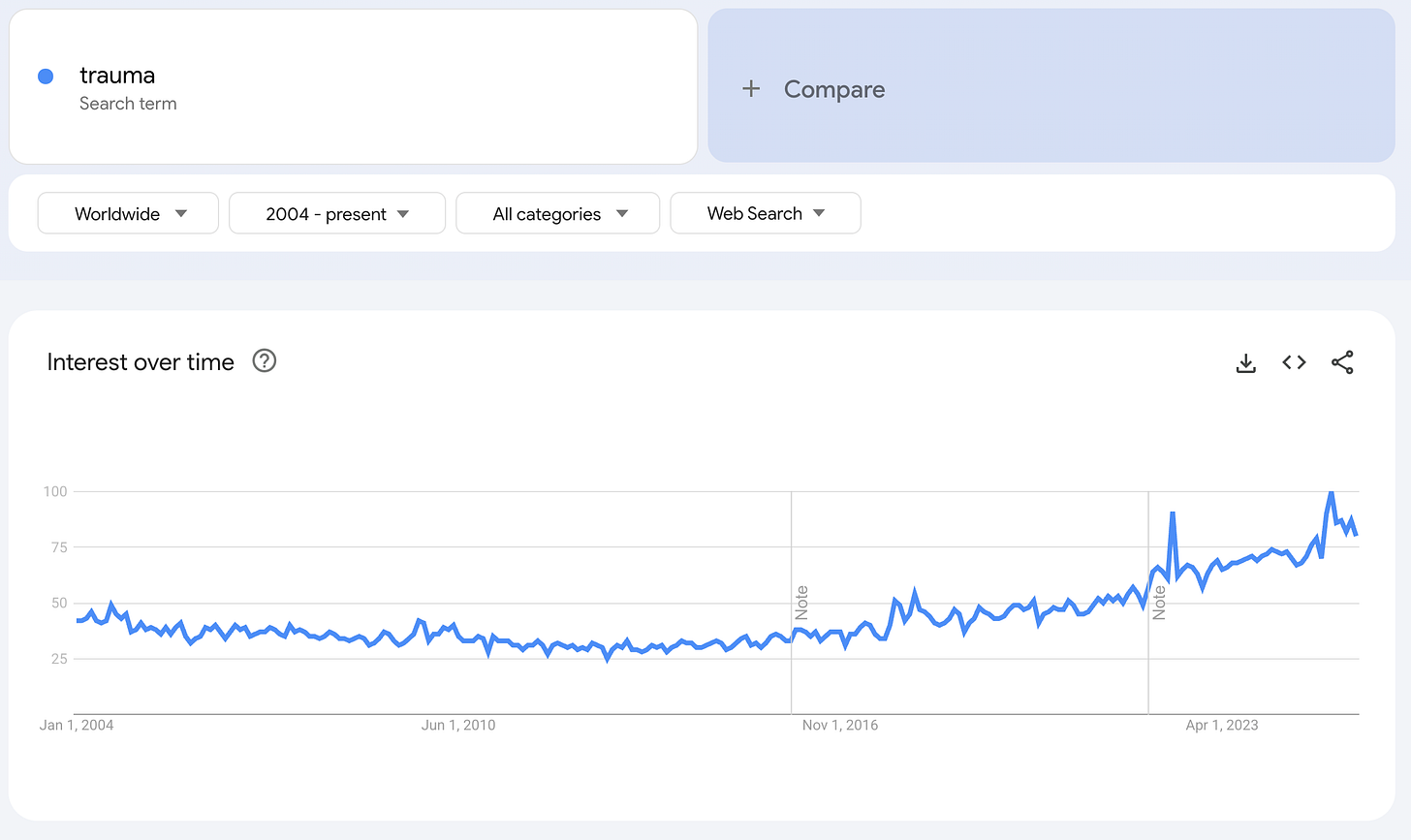

Recently I became captivated by this topic of trauma because from what I was seeing online, it seemed like there was this big surge in interest in the topic. All kinds of influencers are talking about how to ‘release’ or ‘heal’ trauma. A quick look at Google Trends suggests interest in trauma is at an all-time high and peaked just this March. Just recently, I had another look at Bessel van der Kolk’s book, The body keeps the score, and was baffled to see that it had more reviews than the first book of A Game of Thrones at a staggering 79,800 reviews. I recently laid out many of the glaring shortcomings of the book in my article The body keeps the score is bullshit.

The issue with the prevailing narrative about trauma is that a lot of it (not all of it) doesn’t account for how the brain actually works.

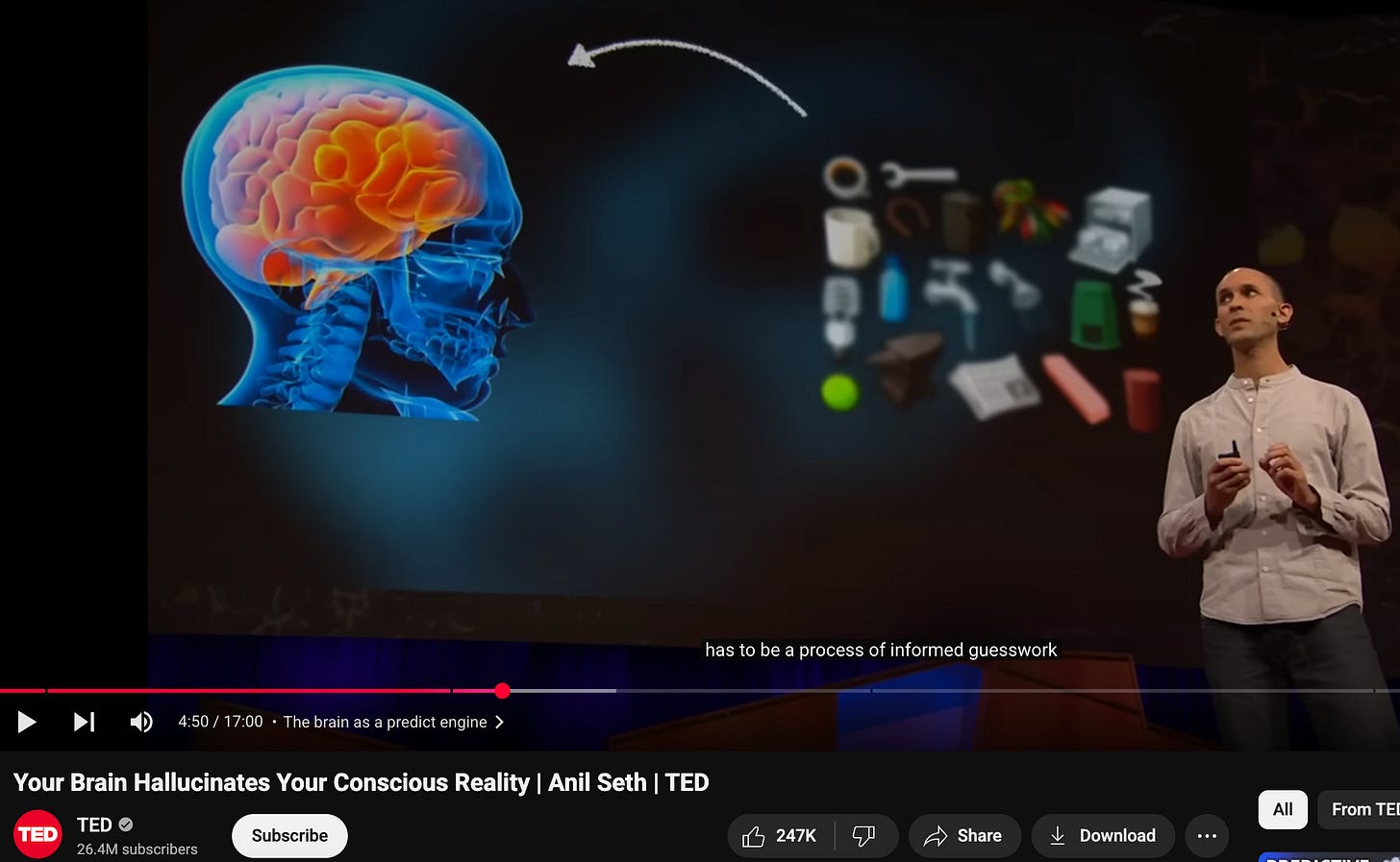

As neuroscientist Anil Seth has explained, your perception is essentially a “controlled hallucination.” That is, reality is your brain’s best guess of what’s going on. Again, the reality you perceive is a sophisticated guess, a prediction of what’s going on.

Several years ago in Amsterdam, I decided to take some magic truffles and hang out in the park. The idea was that I would hang out in the park, feel the cool breeze on my skin and soak in the sun with my enhanced sensory capabilities. Instead, I got an artificially weird experience of nature. While looking out at the grassy hill illuminated by the sun, I felt the breeze in my hair and in the corner of my eye, I saw the reeds on the river swaying. These sensations generated the nonsensical prediction that the source of the wind was train rapidly whizzing by. Alarmed, I quickly jumped to the side only to realize a second later that there was no train and there couldn’t be a train.

Worried there might be bystanders, I pretended to inspect my foot as if I had leapt to the side because I stepped on something sharp. I resisted the urge to bite my fingernails and walked into the forest. More quick thinking allowed me to narrowly avoided getting my leg ripped off by the alligator hiding in between two trees. I let out a quiet “oh shit” before realizing the alligator was in fact, a dried out log.

Anil Seth uses the experience of psychedelics as an example of how weird things can get when you take a substance that screws with the prediction function of the brain. You’ve probably experienced this yourself when you mistook a bag in a dark room for a cat or dog.

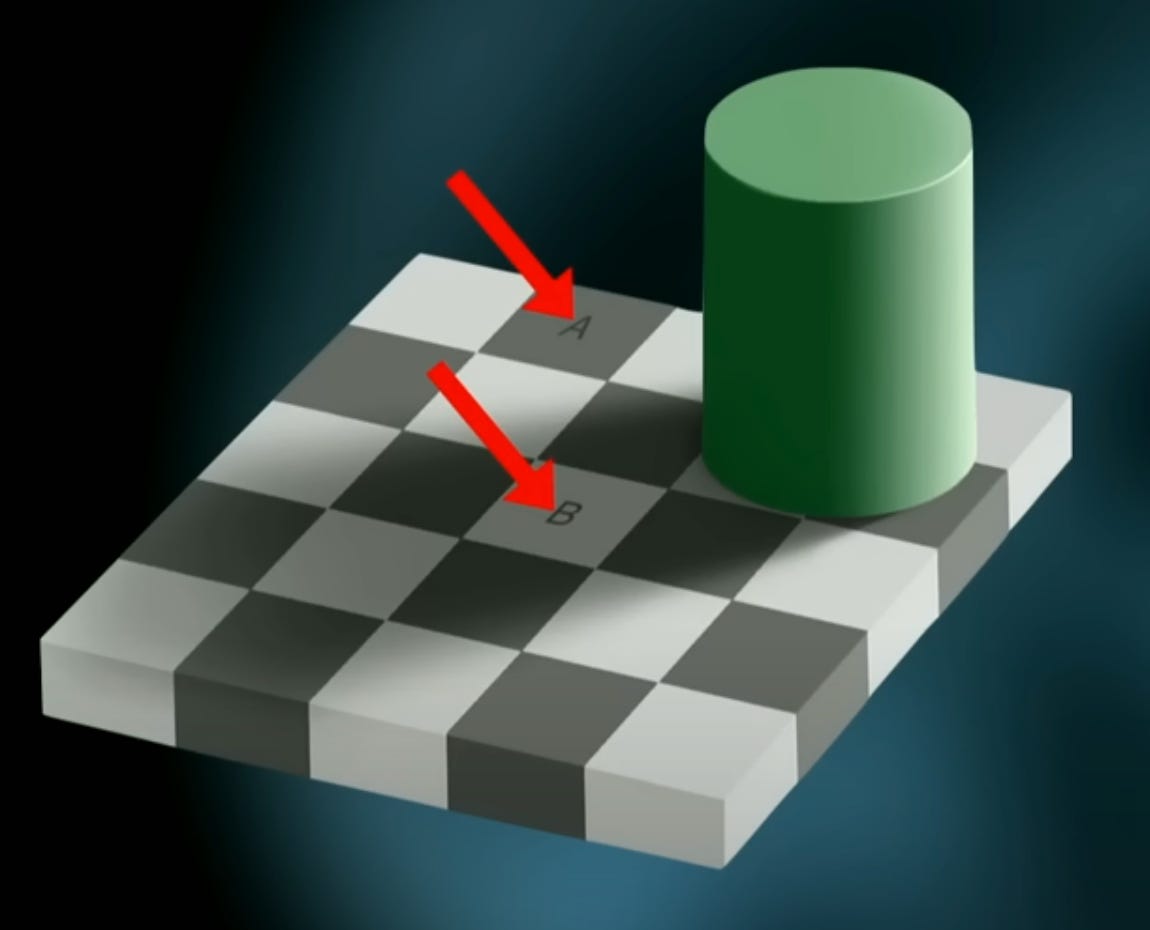

This is why optical illusions work, your brain is tricked by the context. Look at the image above. A and B are actually the same shade of gray, but because of the placement of the object, the brain reasons that because that green thing is casting a shadow and B is in the shadow, B must be lighter than A.

There are even auditory illusions like the McGurk effect. You can trick people into hearing “fa fa fa” or “ba ba ba” by having them view someone’s mouth moving as if they’re saying “ba ba ba” when the audio is actually them saying “fa fa fa.”

There are all kinds of examples of the predictive nature of the brain. For example, Dr. Eliana Vassena of the department of Experimental Psychology from Ghent University describes in a paper how brain scans reveal we predict (expect) greater reward from more difficult tasks. This may explain why some women play hard to get - they are attempting to artificially enhance men’s satisfaction with dating them. This also hints that the reason people can waste so much time doing busywork because they mistake the experience of exerting effort for value. It could also explain why perfectionists take forever to put out their goddamn Youtube videos on their main channel: they endlessly tweak minute details as they unconsciously expect to feel more happy about the video as a result.

So what does this have to do with mental or physical health?

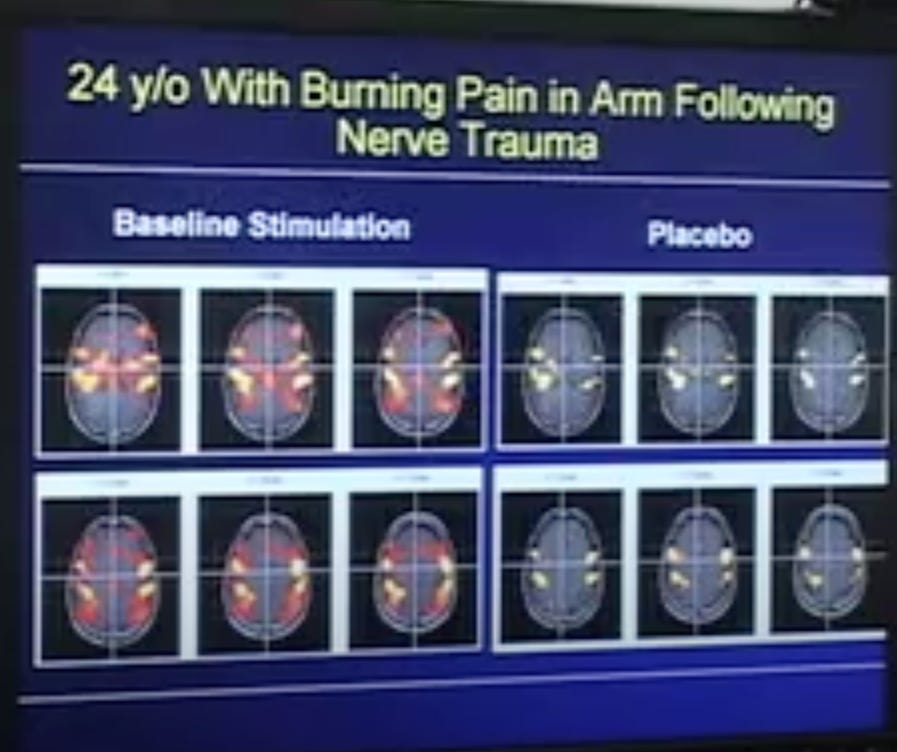

Stopping burning pain, for free

Researchers out of Stanford took one man’s terrible burning pain in his arm from a crush injury from a 7/10 to 3/10 simply by telling him that they gave him a powerful pain-reliever. In reality he hadn’t received an actual analgesic substance yet. Brain scans of his brain even reflected that indeed, he must be feeling dramatically less pain. This power of prediction has been known for quite some time. T. C. Graves first defined the “placebo effect” in a published paper in The Lancet in 1920.

A 2007 paper titled A meta-analysis of the placebo response in complementary and alternative medicine trials of irritable bowel syndrome investigated various trials on irritable bowel syndrome from 1970 to 2006 and found that the placebo response rate is significantly high, 42.6%. Irritable bowel syndrome can be debilitating with its unpredictable cramps and sharp pains, persistent bloating and episodes of urgent diarrhea or uncomfortable constipation. Yet, a simple shift in mindset had a significant therapeutic effect in these people. Further, the placebo response rate increased with more office visits. Better placebo response from more office visits was also observed in people with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

Each office visit modified the prediction model in these people’s brains and simply changing their predictions about the course of the disease lead to less actual distress from the disease.

The boot nail guy was experiencing the opposite of the placebo effect, a “nocebo” effect. Reviews of randomized controlled trials of fibromyalgia, a condition thought to sensitize the person to painful sensations, found that the nocebo effect was to blame for 67.2% to 81.7% of adverse effects in people trying new drugs for the condition. That is, as many as 80% of the side effects people experienced in these trials arose merely because they expected them.

Data suggests 1 in 5 people can experience significant improvements in their depression symptoms merely from the thought and expectation that their medicine would help them (as well as other factors like attention from kind, warm staff). That is, they were getting benefits from a sugar pill with no active ingredient. A 2021 meta analysis on depression found placebo response rates to be as high as 21%.

In fact, another study explains how the flip side of that is also true. When people are told that there is a 50/50 chance that they’ll get an antidepressant or a placebo, an inactive sugar pill, their expectations for improvement are lowered. They figure ‘well, I probably got the placebo, this isn’t going to do anything for me’ and their expectations are lowered, which leads to worse outcomes. That is, even if they get the drug, just having low expectations lowers the actual effectiveness of the drug.

It’s been found many times that people experience better outcomes when it’s the type of trial where they give them either one type of antidepressant or another. That is, they know for sure that they’re getting a drug, they just don’t know which type it is.

A 2019 study in the Journal of Affective Disorders even found that optimistic expectations meant better outcomes with therapy.

Abigail Shrier, author of Bad Therapy: Why the kids aren’t growing up explained on the Joe Rogan podcast that:

Paul McHugh who used to be the head of the John's Hopkins Psychiatry department looked at vets combat vets in America and Israel. What he wanted to know was why was there less PTSD among the combat vets in Israel and one of the things he noticed was that they treat them very differently.

When an Israeli soldier saw something traumatic, a traumatic potentially traumatic event, maybe an IED exploding, their buddies torn apart or killed, they took them out of battle and they said “listen just so you know, your reaction is totally normal. We're sending you home for a few weeks. You're going to feel better, and then we're going to put you right back. You're going to recover and we're going to put you right back with your men.”

With America, when someone had seen something horrific, they would pull them out of battle, they would meet with a therapist who would tell them: “you have the symptoms of PTSD. Your government did this to you and it's possible you may be suffering with this chronically” and they didn't recover at the same rates.

You’ve probably realized by now where I’m going with this.

How much of our issues come from people telling us we have issues?

This isn’t even to say that therapy can’t be helpful. However, telling someone to “go to therapy” is like telling them to “eat a healthy diet.” That could mean a number of things. Not all therapists are the same and not all therapeutic techniques are the same.

A focus on what to do rather than too much discussion of what happened likely have different outcomes.

Absolutely so relevant for today’s victim mentality generation.

Bravo! I love this read! Thank you!